Terrain piece 4 needs to go. It doesn’t create interesting situations in play, and it’s difficult to work with. We need to replace it with something that leads to challenging decisions, and preferably the replacement should be a simpler shape that doesn’t raise rules problems.

Of course, saying that the new piece should “lead[ ] to challenging decisions” isn’t very useful by itself. How does a terrain piece do that? We need to develop some new rules that tell us how terrain in Over the Next Dune works before we can figure out what will work well.

1. “Thick” terrain pieces and “thin” ones involve different decisions.

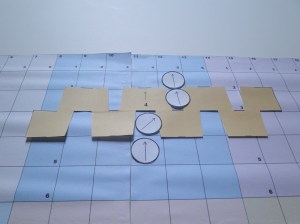

Take a look at piece 6. It’s a 5×3 block. Moving across it vertically will bog a player down for an entire turn, plus part of a second. Getting across it horizontally is . . . well, suffice it to say that that’s not a good tactical move.

In my experience, piece 6 is usually treated as if it just walls off the spaces it occupies. No one wants to go near it, lest they end up in a turn-wasting slog. The decision players make when they look at it is, “how do I get where I’m going, given that I can’t use that part of the board?”

Piece 1, by contrast, is very small–a 5×1 line. Players don’t love crossing it, but they’re willing to do so if they’re already close enough that going around would be slower, or if the searchers make going around unwise. The decision here isn’t about how to avoid the piece, but rather whether to avoid it.

2. Terrain with a variety of widths creates different incentives in different places, and is more interesting as a result.

Piece 5 is as thick as piece 6 in some places, as thin as piece 1 in others. In my experience, those differences in width matter. Where piece 5 is thin, the players consider going over it; where it’s thick, they avoid it. This single piece combines the decisions involved in the other two, and makes each of them more interesting: is this spot thick enough that it should be treated as walled off? Is there a route across the terrain that’s more favorable? It’s much harder to develop a simple rule of thumb regarding piece 5, and that makes the piece a lot more engaging to think about and deal with.

3. Both terrain’s vertical and horizontal lengths are relevant during play.

In general, the solution to terrain in OtND is to shift sideways before getting to it. Piece 5, however, creates a vertical channel as well as a horizontal barrier. It therefore makes the sidesteps that are effective against most terrain pieces tricky. Getting around piece 1 is much harder when piece 5 is in the way.

Terrain piece 3 can do much the same thing. Players are much more inclined to go left around it than they are to go right and cross its vertical length.

Since sidestepping is so effective in general, I think it’s healthy for the game to make it more challenging when an opportunity to do so arises. That means more pieces with a significant vertical dimension.

4. Bigger pieces have more of an impact than smaller ones.

This is probably obvious, but it’s worth noting so that it’s not overlooked. Piece 1 is easy to work around. Piece 6, by contrast, strongly pushes players away. Terrain piece 5’s vertical length affects more decisions than piece 3’s. If the goal is to have a terrain piece matter, making it bigger is a good place to start.

Those rules leave a lot of possibilities. What about something like (pardon the terrible art, please ignore the underscores):

x x x x x

__x x x

____x

__x x x

x x x x x

That’s big, has lots of vertical length, and has different widths at different points that capture both the “thick” and “thin” decisions. We could also make it more complex:

x x x x

__x x x

____x

__x x

x x x x x

Both of these have a flimsy middle–not as flimsy as the old piece 4’s, but potentially a problem. How about:

x x x x

__x x x

____x x

____x x

x x x x x

Hm. That looks like it has potential. Let me know what you think, and if there are no serious objections I’ll update the print-and-play file with the new piece.