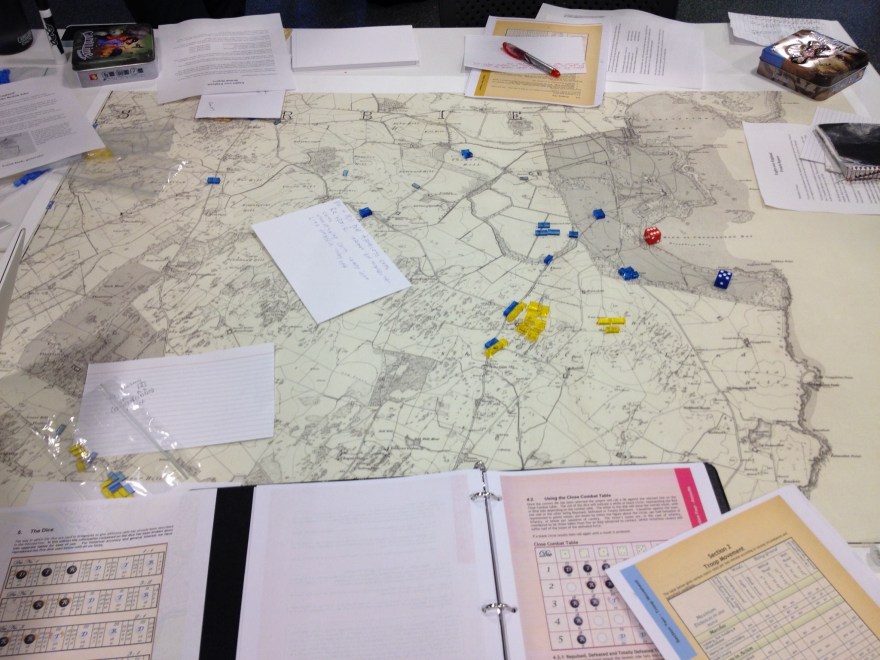

Yesterday I played a favorite wargame against a relatively new player. My opponent played well, but I was able to set up a turn in which I removed almost all of his heavy hitters. The following turn I cleaned up what remained of them, and from that point on my opponent was on the wrong side of rock-paper-scissors. I had thickly-armored units, nothing on his side of the table could deal with them, and we could both see the writing on the wall.

It’s a rule in this particular game that if you ever lose your general, you’re out. One purpose of that rule, I believe, is to give players who are losing an out. When the tide turns against you, you can snatch victory from the jaws of defeat by getting to the enemy leader and taking them off the table.

Knowing that losing my general could cost me this game that was otherwise in the bag, I did the only logical thing: I backed up. Way, way up. My general–my most important piece–ended the game tucked into the corner of the board, far from the light infantry-versus-heavy armor scrum that was deciding the game in the middle of the table. The one remaining weak link that my opponent was meant to be able to exploit stayed out of range, entirely safe.

Yesterday’s opponent was sporting about all this, but in the end he simply conceded. The “out” that was supposed to give him a chance wasn’t there. Why should he keep playing?

For that matter, why should I? It was all over but the die-rolling. There was no fun in grinding out the remainder of the exercise.

I see in that single play a microcosm of two issues that plague competitive games in general:

1. The best strategy is often to minimize risk, but that’s also the least fun strategy. We love the exciting moments in games, but those are the times when something could go wrong. It’s usually better, from a purely victory-focused standpoint, to avoid excitement. My game would have been more fun if I’d gotten my general stuck in . . . but hiding off in the corner was the smart play, and I knew it.

To counteract this, we as designers should reward engaging, risk-accepting play. That’s the approach that makes the game the most fun, both for whoever’s in the lead and for whoever’s trying to come from behind. Allowing–or, worse, encouraging–risk minimization means that decisions stop being interesting; it doesn’t take long for that to sap the fun out of the experience.

2. The game doesn’t end when it’s been decided. Although my opponent and I could tell that the game was over, the rules couldn’t. We had at least two turns of largely decision-less mopping-up to get through before an official end state was reached. Luckily, we were both of the same mind about whether conceding was appropriate; had we not been, it could easily have taken the rest of the evening to grind out the conclusion.

Again, this is a problem that we as designers need to confront. It’s not always easy to judge when a game is “actually over,” especially when the game is complex. Nevertheless, we should always be keeping an eye on the data, and refining the game-end conditions where possible. If it turns out that X is a good predictor of who will win, it’s worth considering whether attaining X should itself mean victory.

Competitive games have suffered from these problems for thousands of years. I don’t expect that we’re going to be able to address them instantly; even as I point at these issues, I have to acknowledge that I struggle to respond to them in my own work. Nevertheless, I feel that it’s worth recognizing them. Dealing with these two problems is, I think, one of the next horizons in game design.